Aeschylus Biography

Most records of Aeschylus's life have been lost in the 2,500 years since his birth. What does remain is attributed to early Greek biographers, and there is still disagreement among contemporary scholars over the exact details of Aeschylus's life. Aeschylus is estimated to have been born in 525 or 524 BCE, and he was likely raised west of Athens in a small town called Eleusis.

Aeschylus was born into an era of social change and political uncertainty. When Aeschylus was roughly 15, Athens underwent major reform when the previous leader was overthrown and Cleisthenes came to power. Cleisthenes is credited with establishing democracy in Athens, which, over the coming years, was constantly threatened by foreign invaders and domestic politicians.

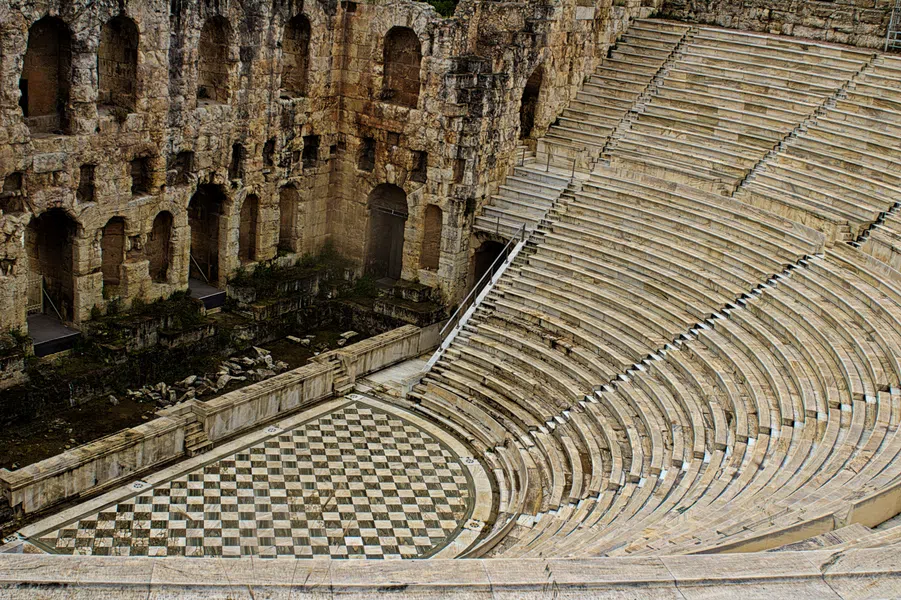

Fig. 1: Aeschylus was raised in Athens when it was reformed to become a renowned democracy.

One of the most decisive events in Athenian history was the Persian Wars. The war began in 499 BCE and pitted the Greek forces against the enormous Persian Empire. Aeschylus himself fought and was wounded in the Battle of Marathon when he was 35. The Greeks won, but Aeschylus's brother was killed in battle. When the Persians invaded again ten years later, Aeschylus again fought in the battles of Artemisium and Salamis.

Aeschylus used his experience in the war as inspiration for his play The Persians (472 BCE), the earliest of his surviving works. Aeschylus began competing in drama competitions in 499 BCE. Every year, the Great Dionysia pitted three prominent Athenian dramatists against one another. The playwrights would each produce three tragedies (either connected or not) and one satyr play. Aeschylus competed against famed ancient dramatists, including Sophocles and Phrynichus. Aeschylus won his first competition in 484 BCE.

A satyr play inserts comedic elements and backdrops into the structure of a tragedy to create a light-hearted, humorous hybrid of tragedy and comedy.

Aeschylus's career as a dramatist continued until his death. His works were incredibly successful at the Great Dionysia and won most years. He did, however, lose to Sophocles in 468, to which Aeschylus responded with his winning Oedipus trilogy the following year. Aeschylus is believed to have written approximately 90 plays (both tragedies and satires) over the course of his successful career, but only seven tragedies have survived in their entirety and can be read today.

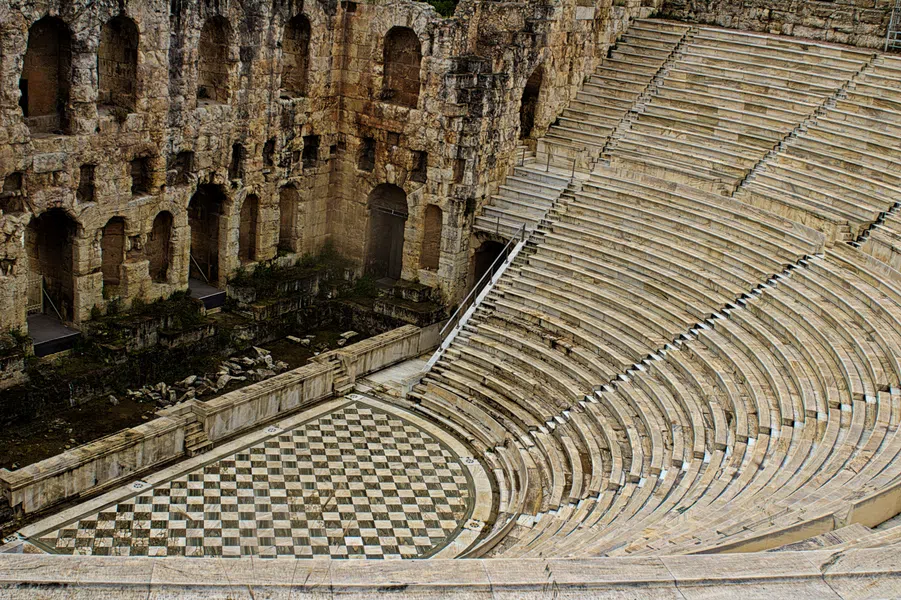

Fig. 2: Aeschylus's plays were performed for the public every year during the Great Dionysia, a festival honoring Dionysus.

Aeschylus had two sons, Euphorion and Euaeon. Both followed in their father's footsteps and became major dramatists. Euphorion won first place in the 431 BCE competition against Sophocles and Euripides.

Aeschylus Cause of Death

Aeschylus died in 456 or 455 BCE. He was staying in the city of Gela and was about 69 at the time of his death. According to 1st-century biographer Valerius Maximus, the great dramatist was killed when an eagle dropped a tortoise on his skull, believing his bald head to be a shiny rock. Many scholars believe this story was fictionalized purely for comedic effect. Pliny the Elder, also from the 1st century, wrote Aeschylus had been purposefully staying outdoors in the open to avoid a prophecy warning he would be killed by a falling object. Again, these accounts are impossible to verify.

Fig. 3: According to legend, Aeschylus died after a tortoise was dropped on his head.

Regardless, Aeschylus was so respected he was thrown a public funeral in Gela, complete with dramatic performances and sacrifices. His gravestone speaks only of his military career and does not mention his theater contribution. It reads:

Beneath this stone lies Aeschylus, son of Euphorion, the Athenian,

who perished in the wheat-bearing land of Gela;

of his noble prowess the grove of Marathon can speak,

and the long-haired Persian knows it well."

— Anthologiae Graecae Appendix, vol. 3, Epigramma sepulcrale. p. 17.

Aeschylus Accomplishments

Aeschylus is commonly referred to as the father of tragedy and is credited as the first Greek dramatist to popularize the genre of tragedy. Together with Sophocles and Euripides, Aeschylus is one of the only ancient Greek dramatists to have a work survive in full. According to Aristotle, Aeschylus revolutionized drama by enabling his characters to interact with one another instead of only with the traditional chorus. By reducing the role of the chorus and heightening dialogue and conflict between multiple characters, Aeschylus increased tension in his dramas and pushed the plot in entirely new directions.

Fig. 4: Aeschylus revolutionized drama by enabling his characters to interact with one another instead of just the chorus.

Aeschylus was also notable for using scenic effects, stage costumes, and available technology to heighten the emotion and believability of the play. Although other dramatists existed before him, their work has long been lost and unavailable for study. As seven of Aeschylus's plays survived in their entirety, the study of tragedy as a genre begins with Aeschylus's work.

Aeschylus's use of language was also an important accomplishment. Instead of having static characters and tedious plot lines, Aeschylus's characters had a strong command of language characterized by emotional intensity. His plot lines were original and nuanced, taking Greek theater to new intellectual heights. And he was able to examine the problem of evil in his discussion of religion, war, and the law. Aeschylus was so successful in writing drama that his plays stand the test of time and are still studied for their literary value today.

Aeschylus Plays

Although Aeschylus was believed to have written roughly 90 plays, only 80 titles are known, and only 7 plays remain intact. Some of his most famous are The Persians (472 BCE), The Oresteia (458 BCE), and Prometheus Bound (date and authorship disputed).

The Persians (472 BCE)

Based on Aeschylus's own experience fighting in the Persian War, The Persians is unique from other classical tragedies in that it centers around contemporary events and recent history rather than mythical Greek history of the past. The Persians is set in the Persian capital, directly after Persia forces were defeated at the Battle of Salamis.

The Persian King Xerxes has not yet returned home. His mother, Atossa, is dismayed when a messenger brings news of her country's defeat at the hands of the largely-outnumbered Greek forces. Atossa travels to her husband's tomb to seek wisdom and solace.

His ghost appears and tells Atossa their son's defeat was a punishment from the gods for Xerxes's hubris in building a bridge outside of his boundaries. King Xerxes finally returns home from the war, defeated and humiliated. He does not understand how he lost and laments the unsuccessful battle.

The Oresteia (458 BCE)

The Oresteia is the only known extant ancient trilogy to still exist in its entirety, meaning it is the only known ancient trilogy scholars recognize as being complete and unaltered. The three plays, Agamemnon, The Libation Bearers (Choephoroi), and The Eumenides, are closely related and tell the tragic story of King Agamemnon of Argos.

In the first play, Agamemnon returns home victorious from the Trojan War. His wife, Clytemnestra, is out for revenge on Agamemnon, who sacrificed their daughter to appease the gods during the war. The prophetess Cassandra, who is also Agamemnon's lover, predicts both of their deaths at Clytemnestra's hands. When Orestes, Clytemnestra and Agamemnon's son, learns of his father's death in the second play, he murders his mother and her lover.

The Furies aim to punish Orestes for murdering his family. He is saved by the god Apollo, who shares some of the blame for Clytemnestra's death. The gods declare a trial is necessary, and Orestes is eventually acquitted.

The Furies are typically presented as vengeful deities that harshly punish humans for their crimes. The Furies considered matricide sacrilegious and aimed to punish Orestes for his crimes. In order to appease the Furies, Athena offers the Furies new roles as goddesses of morality and justice to appease them when Orestes is acquitted.

Prometheus Bound (date disputed)

Although ancient sources list Aeschylus as the author of Prometheus Bound, his authorship has been disputed since the 19th century. The original production date has also been disputed, with scholars listing it anywhere from the 480s BCE to the 410s BCE. Prometheus Bound centers around the punishment of the ancient Titan Prometheus. After defying Zeus and providing humans with fire, Prometheus is chained to a rock in a barren mountainside, unable to move.

Other gods are sympathetic to Prometheus, but none would dare to defy Zeus. Prometheus is visited by deities and Io, a former lover of Zeus, who is now one of his victims. Seeing her strengthens Prometheus's resolve against the tyrannical king of gods. When Prometheus refuses to tell Zeus what union could cause his downfall, Prometheus is sent to the underworld for further torture.

Fig. 5: Prometheus is visited by the Oceanids, who console Prometheus and make up the chorus of the play.

Aeschylus Quotes

Below are some of Aeschylus's most famous quotes.

Zeus, who guided mortals to be wise,

has established his fixed law —

wisdom comes through suffering.

Trouble, with its memories of pain,

drips in our hearts as we try to sleep,

so men against their will

learn to practice moderation.

Favours come to us from gods

seated on their solemn thrones —

such grace is harsh and violent." (The Orestia, Agamemnon, 175-183)

This quote directly speaks to theodicy, which seeks to answer the question, "if god is pure goodness, why does he enable evil?" For this ancient speaker, the gods allowed pain to exist in order to catalyze wisdom and grace. The gods themselves are not presented as cruel, but they allow harsh things to happen to a person so they can learn from their past pain and make a better future. Theodicy is still an important issue in contemporary religion, and this quote reminds today's readers one can only attain wisdom through experience, both good and bad.

IO: Then what gain is it for me to live? Nay, why

did I not fling myself forthwith from off this

rugged rock, that falling on the plain I had

been quit of all my pains? Better once for

all to die than to fare ill all one's days." (Prometheus Bound, 748-752)

In a discussion between Io and Prometheus about suffering, Io declares she would rather be dead than suffer her fate every day. Prometheus seems to agree. While Zeus has left them alive, their torturous punishment is more painful than death would be. They have their lives, but their standard of living has decreased so significantly they would rather be dead. Io is forced to wander the earth aimlessly, never able to settle down, while Prometheus is chained in one place, never able to leave.

PROMETHEUS. There is no ill-treatment, no contrivance, by which Zeus will induce me to reveal this secret, until these degrading bonds have been unloosed. So let him hurl his blazing fire, let him throw everything into turmoil and confusion with his white feathers of snow and his thunders rumbling beneath the earth: none of that will bend me to make me say at whose hands he is destined to fall from his supreme power. (Prometheus Bound, 986-996)

In this impassioned speech, Prometheus asserts his will over his tormentors. He says it does not matter what Zeus or the other gods do to him. He will stand firm in his beliefs and will not yield to Zeus's demands. Prometheus's defiance gives him some power over Zeus, even as Prometheus is kept locked in chains.

Aeschylus - Key Takeaways

- Aeschylus was one of the first Greek dramatists to write tragedies, and he revolutionized the genre by adding more characters and enabling them to speak to one another.

- He was born around 525 or 524 BCE and grew up during a time of political uncertainty in Athens.

- He, Sophocles, and Euripides are the only three ancient Greek tragedians to have a surviving extant work.

- He is said to have died after an eagle dropped a tortoise on his head, believing his bald head to be a rock on which it could crack the tortoise.

- Aeschylus is most famous for his plays The Persians (472 BCE), The Oresteia (458 BCE), and Prometheus Bound (date unknown), although ownership of Prometheus Bound is disputed.

Similar topics in English Literature

Related topics to American Drama

How we ensure our content is accurate and trustworthy?

At StudySmarter, we have created a learning platform that serves millions of students. Meet

the people who work hard to deliver fact based content as well as making sure it is verified.

Content Creation Process:

Lily Hulatt is a Digital Content Specialist with over three years of experience in content strategy and curriculum design. She gained her PhD in English Literature from Durham University in 2022, taught in Durham University’s English Studies Department, and has contributed to a number of publications. Lily specialises in English Literature, English Language, History, and Philosophy.

Get to know Lily

Content Quality Monitored by:

Gabriel Freitas is an AI Engineer with a solid experience in software development, machine learning algorithms, and generative AI, including large language models’ (LLMs) applications. Graduated in Electrical Engineering at the University of São Paulo, he is currently pursuing an MSc in Computer Engineering at the University of Campinas, specializing in machine learning topics. Gabriel has a strong background in software engineering and has worked on projects involving computer vision, embedded AI, and LLM applications.

Get to know Gabriel