Life in White Noise is viewed as if it is data on a screen, pixabay

White Noise Summary

Written in the style of a dark family comedy but set in a surreal and industrial atmosphere, DeLillo’s novel is made up of three sections: "Waves and Radiation," "The Airborne Toxic Event," and "Dylarama."

"Waves and Radiation"

The first section of the novel is dedicated to building the setting of 1980s America. Not driven by the plot, it instead focuses on the cultural backdrop of television, electronic media, and the plethora of sounds made by the world. Behind the characters' relative comfort and consumer ease, however, lurks the feeling of impending catastrophe.

The novel is set firmly in the world of television and digital media, pixabay

The novel centers around the life of Jack Gladney, the chair of the Hitler Studies department at the College-on-the-Hill in the fictional Midwestern American town of Blacksmith. Though Jack's academic career focuses on Hitler and Nazi Germany, he embarrassingly does not know any German and begins to take German lessons in secret. Jack's third wife, Babette, gives aerobics training to seniors and reads tabloids to an elderly man.

The section is also interspersed with scenes of Babette's young son Wilder spending an entire day crying for seemingly no reason, men in Mylex suits mysteriously dying during a school evacuation, an airplane nearly crashing, Jack's teenage son Heinrich playing chess by mail with a convicted murderer, and Babette having difficulties with her memory.

Mylex is the fictional name for the material of protective suits worn by the emergency crews during White Noise's disasters. It is a play on the word Mylar which is an actual material used for insulation and heat-resistant clothing.

"The Airborne Toxic Event"

The novel's second section begins with the story's inciting event—a chemical leak caused by a train car derailing from the tracks. The train car spills an uncontrollable amount of toxic gas called Nyodene D into the environment. The Gladney family watches from a distance as Jack and Babette try to remain calm and continue life as though no real threat is emerging.

Inciting event: the incident that begins the narrative's action sequence, often establishing a problem that the characters try to solve

A cloud of smoke rises from the accident while emergency workers in Mylex suits spray the spill with another chemical. The Gladney family listens intently to an emergency broadcast on the radio. The broadcast lists symptoms of chemical exposure to Nyodene D, then revises them, and later revises those revisions. While listening, Jack and Babette's daughters begin to show signs of exposure. Their signs match the current updates, revealing to Jack and Babette that their daughters are susceptible to the authority of the radio's voice—they experience the symptoms they are told to have. Eventually, the radio suggests that an exposure symptom is a feeling of déjà vu.

"Déjà vu" is a French expression for the feeling of having already experienced something that is happening for the first time. Déjà vu becomes an important example of White Noise's theme of repetition and simulation. How can one know if an experience is real if it seems to have already happened?

The Mylex-suited clean-up crews in White Noise would have looked similar to these emergency responders in the famous 1986 Sandoz chemical spill in Switzerland, Wikimedia Commons

The Mylex-suited clean-up crews in White Noise would have looked similar to these emergency responders in the famous 1986 Sandoz chemical spill in Switzerland, Wikimedia CommonsThe chemical leak begins a mass evacuation of the nearby towns and cities, causing the characters to suddenly become aware of their bodies' vulnerability to man-made forms of death. Before the family reaches the emergency shelter, Jack has to refill the car's empty gas tank. He briefly exposes himself to the toxic air and begins to worry about death and his own mortality.

"Dylarama"

At the start of the novel's final section, life has seemingly returned to normal: "the déjà vu crisis centers closed down. The hotline was quietly discontinued. People seemed on the verge of forgetting" (Chapter 29). However, the uncertain feeling of impending catastrophe lingers. Jack continues his unsuccessful German lessons, and Babette has ongoing trouble with her memory.

Jack finds one of Babette's Dylar pills in the trashcan. Not knowing what it is, he takes it to one of his colleagues, who tells Jack that the pill is meant to inhibit the fear of death. Jack confronts Babette, and she confesses not only to taking it regularly, but also to her affair with Mr. Gray, the man whose company produces the drug. Terrified of dying, Babette offered Mr. Gray her body in exchange for pills. Dylar's effects eventually started to diminish and ultimately stopped working on Babette. She is left with a waning memory and bouts of déjà vu.

They could not initially test the effectiveness of the drug on animals because animals do not experience the fear of death.

Seeking revenge on Mr. Gray, Jack researches Dylar and Gray's company. His search reveals that Mr. Gray's real name is Willie Mink. Jack decides to track him down and kill him. He finds Willie alone, watching TV with no sound, at the Roadway Motel. Willie is a tragic, sad figure who is barely conscious and surrounded by piles of Dylar pills that did not make it into his mouth. When Jack speaks to Willie, he realizes that the drug has made Willie susceptible to spoken suggestions. Jack says, "Falling plane," and Willie begins acting like he is in a plummeting aircraft.

Note Dylar's side effects of déjà vu and its subjects' mimicry of things on command. Here White Noise makes a nod to Sigmund Freud’s concept of the “death drive,” which he defines as “the compulsion to repeat.”2 The tragic irony that White Noise displays here is the desire to ward off death actually repeats it in new ways.

Jack shoots Willie with his revolver and then puts the revolver in Willie's hand to make it look like a suicide. Willie, however, isn't dead. He picks up the gun and shoots Jack in the wrist. Jack realizes that killing Willie would be senseless, so he drives Willie to a church run by German nuns. As they tend to the men, the nuns reveal they do not believe in God.

In the closing scene of the novel, Jack's son Wilder rides his tricycle through traffic across a highway. A few women nearby watch in horror, unable to reach him. Once Wilder reaches the other side of the highway unharmed, the tricycle falls over and he begins to cry.

White Noise Characters

DeLillo uses the characters in the novel to represent the various absurdities of modern living.

Jack Gladney

A middle-aged professor of Hitler studies, Jack is the narrator and focal character. He has been married three times, is terrified of dying, and uses his status as a distinguished professor as emotional armor against his sense of threatened masculinity.

Babette Gladney

Babette is Jack’s third wife and the mother of the young Wilder. Babette and Jack discuss, with an impending sense of dread, which one of them will die first. Her own fear of death pushes her to undertake the search for a miracle drug.

Heinrich Gladney

Heinrich, Jack's teenage son, is described as a "comically intimidating nerd".1 Fascinated by the dangerous and dramatic aspects of modern life, Heinrich plays chess by mail with a convicted killer on death row.

Denise Pardee and Steffie Gladney

Denise is the eleven-year-old daughter of Babette. She reads the Physician's Desk Reference and is concerned with Babette taking the mystery drug Dylar. Steffie is Jack's nine-year-old daughter who is caring and neurotic. Denise and Steffie are portrayed as a pair of sitcom sisters—both are wry, intelligent, and comically bossy.

Willie Mink (Mr. Gray)

Willie Mink is the tragic figure who invents Dylar and has an affair with Babette. His medical venture fails, and he becomes mentally and physically damaged by his addiction to his own medicine.

The grayness of Willie's alias ("Mr. Gray") suggests being stuck between life and death, as though in a kind of prison.

White Noise Quotes

Below are some of the most important quotes in White Noise.

All plots tend to move deathward. This is the nature of plots. Political plots, terrorist plots, lovers' plots, narrative plots, plots that are part of children's games. We edge nearer death every time we plot" (Chapter 6).

DeLillo toys with the various denotations of the word plot, intermingling the meanings to give this quote more significance. Plot as a noun refers to a plan of action. As a verb, plotting is malevolent scheming devised in secret by a group of conspirators. A plot is also the series of events that make up the action of a story. Plot is a word for a piece of land, and finally, a plot is a grave, as in "burial plot."

Consider Mr. Gray's scheming, the characters' preoccupation with death, the government's attempt to cover up the toxic spill, and other events in the novel. DeLillo's fiction highlights this convergence of meanings of "plot," which both pushes the characters together and drives them apart.

Who will die first?" (Chapter 7)

This quote reveals the Gladneys' obsession with death. Even before the toxic chemical spill, the characters question their own mortality. Death follows them around as an ever-present reminder of what will inevitably happen to them. The characters are also willing to go to great lengths to avoid thinking about or answering this question. In fact, many other characters need to escape this question so badly that they start taking Dylar pills, which only bring them closer to the death they try to avoid.

Your genetics, your personals, your medicals, your psychologicals, your police-and-hospitals. It comes back pulsing stars. This doesn't mean that anything is going to happen to you as such, at least not today or tomorrow. It means that you are the sum total of your data. No man escapes that" (Chapter 21).

This quote underscores the conformity of the Gladneys' world that has been intensified by technology. The media controls what people think, their actions, and even their identity. No one is able to escape the influence of technology, which catalogues everything about their lives. People have come to rely so heavily on technology that even their actions are determined for them, as evident in the character's response to what they hear on television and the radio. They behave how they have been programmed to, instead of as individual people.

White Noise Analysis

In order to better understand the novel, this section will examine the title (White Noise) and the most famous passage of the novel ("The Most Photographed Barn in America”).

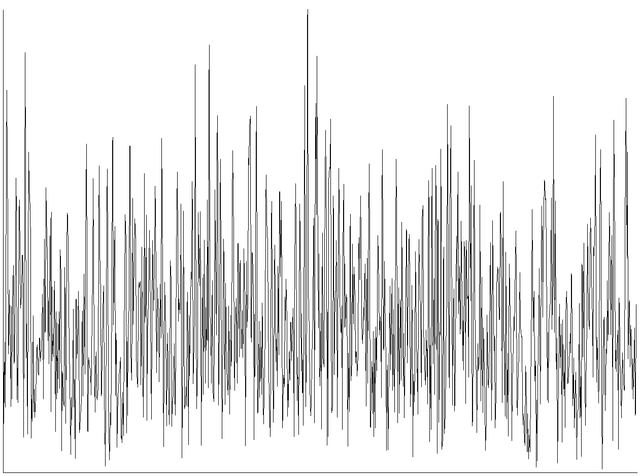

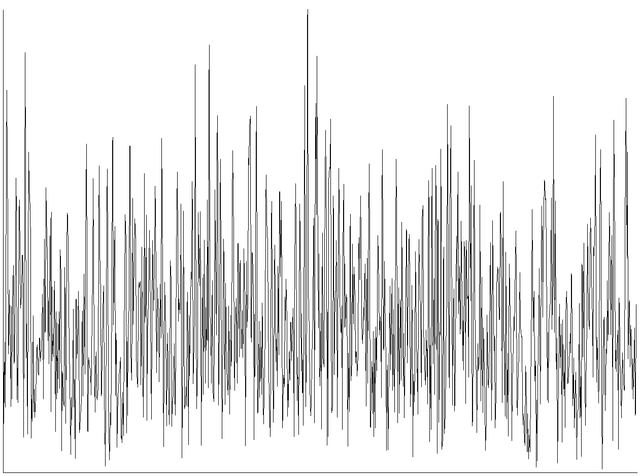

Sound and White Noise

The term “white noise” refers to an audio signal which combines all frequencies at the same intensity. Think of a fan blowing or an untuned radio station—white noise is the noise of static. All of the sounds in the modern US environment of White Noise add up to a single uniform soundscape. This is important in the context of technology, which thrums in the background of every section of the novel.

When Jack stands over Mink with the gun, he experiences all of the sound in the room as white noise: "The intensity of the noise in the room was the same at all frequencies. Sound all around." (Chapter 39)

White noise is also often used to mask other noises because it is a combination in which no single frequency stands out. Instead of being one solitary sound, it is an amalgamation. This speaks to the conformity of the novel, where individuality is snuffed out. Everyone is subject to technology. Each person is a limited piece of the whole. The people themselves do not matter as much as the media and technology they use. The ever-present noise is always "insinuating the sibilant whisper of death into everything."2

A picture of a waveform of white noise, Wikimedia Commons

The Watching of Watching

“The Most Photographed Barn in America” is one of the most widely discussed scenes about the function of technology in postmodern literature. In this section, Jack takes his colleague Murray to a tourist spot nearby called "The Most Photographed Barn in America" (Chapter 3). As Jack and Murray approach the destination, they see a series of billboard signs advertising "The Most Photographed Barn in America." When they arrive, they watch a crowd of photographers milling about. Murray suddenly realizes that no one actually sees the barn. The reason everyone is here is to maintain an image rather than to take one.

The philosophical point of this scene is that this collective watching obscures the original thing being watched. As Murray says in the scene, "Once you've seen the signs about the barn, it becomes impossible to see the barn" (Chapter 3). The collective experience of watching something becomes more important than the object being looked at. This turns the original object into an “occasion” for something social, collective, and vaguely spiritual. Murray contends, "We've agreed to be part of a collective perception" (Chapter 3).

White Noise Themes

The two main themes in White Noise are repetition, simulation, and feedback loops and fear of death.

Repetition, Simulation, and Feedback Loops

DeLillo's novel concerns the many different ways things get repeated. The way a person repeats a plan in order to memorize it, the way a copy of something often stands in for (and sometimes replaces) the original––this is called simulation.

In the digital age, much of society's management is planned with extensive research made by computer simulations of possible events: presidential elections, championship sports games, medical diagnoses, and disaster training. It is this last one, disaster training, which White Noise dramatizes.

As the mass evacuation occurs following the airborne toxic event, the local government utilizes it as an opportunity to research its preparedness for disaster management. When the Gladney family arrives at the emergency shelter, Jack speaks to a technician to register his family and detail his brief exposure to Nyodene D. He sees that the technician is wearing a patch that says SIMUVAC because they are using the real situation as a simulation of a disaster to prepare for future disasters. Therefore, White Noise suggests that the distinction between a real event and its simulation gets significantly blurred.

A feedback loop is another type of repetition apparent in White Noise. Also called "infinite regression," a feedback loop occurs when the output of a system gets picked up and re-introduced into the system, which again becomes part of the output, then re-introduced, and so on and so on. With sound, the hum from a speaker can get picked up by the microphone and then amplified through the speaker, causing a loud whining.

A hall of mirrors, or mirror tunnel, is a visual example of a feedback loop. Each mirror image gets reflected back into another reflection. Wikimedia Commons.

A hall of mirrors, or mirror tunnel, is a visual example of a feedback loop. Each mirror image gets reflected back into another reflection. Wikimedia Commons.

In "The Most Photographed Barn in America," the photographers become absorbed into the image that they are attempting to capture. As with a sound system, too much feedback prevents the system from working the way that it was intended to.

The Fear of Death

White Noise deals extensively with the "unreal" aspects of modern life—simulation, consumerism, and déjà vu's eerie feeling that an event is being re-experienced. Because everything in the modern world is artificial and controlled by humans, death becomes the one thing that the modern world cannot conceptualize. The characters fear death because it is the one thing that breaks up the repetition of their modern life.

The fear of death actually becomes debilitating as the characters obsess over when and how they will die. In an effort to escape the fear of death, Babette, Willie, and many others turn to untested pills. They eventually fall victim to the pills, which bring them even closer to death. Ironically, while trying to escape the fear of death, they bring themselves closer to death than ever before.

White Noise - Key Takeaways

- White Noise is preoccupied with the American media's fascination with disaster and mass catastrophe.

- The style of White Noise's writing is that of a dark family comedy.

- Jack and Babette are both afflicted with the fear of death.

- The names of fictional chemicals in White Noise are Nyodene D and Dylar.

- Déjà vu is the feeling that one has already experienced something that is currently happening.

1. Martin Amis, "Laureate of Terror," The New Yorker, 2011.

2. Sigmund Freud, Beyond the Pleasure Principle, 1920.

Similar topics in English Literature

Related topics to American Literature