An example of two phonetic sounds is the two “th” sounds in English: there is the voiceless fricative /θ/ and the voiced fricative /ð/. One is used to transcribe words like think [θɪŋk] and path [pæθ], and the other is used for words like them [ðɛm] and brother [ˈbrʌðər].

Phonetics and linguistics

Phonetics studies speech sounds from different viewpoints and is broken down into three categories that are studied in linguistics:

- Articulatory phonetics: the production of speech sounds

- Acoustic phonetics: the physical way speech sounds travel

- Auditory phonetics: the way people perceive speech sounds

Phonetics and phonics are often used interchangeably, but they are not quite the same. Phonics is a teaching method that helps students associate sounds with letters and is an essential part of teaching reading skills.

Articulatory phonetics

Articulatory phonetics is:

The study of how humans use their speech organs to produce specific sounds.

Articulatory phonetics is concerned with the way sounds are created and aims to explain how we move our speech organs (articulators) to produce certain sounds. Generally speaking, articulatory phonetics looks at how aerodynamic energy (airflow through the vocal tract) is transformed into acoustic energy (sound).

Humans can produce sound simply by expelling air from the lungs; however, we can produce (and pronounce) a large number of different sounds by moving and manipulating our speech organs (articulators).

Our speech organs are:

- Lips

- Teeth

- Tongue

- Palate

- Uvula (the teardrop-shaped soft tissue that hangs at the back of your throat)

- Nasal and oral cavities

- Vocal cords

Pronunciation in phonetics

Usually, two speech organs make contact with each other to affect the airflow and create a sound. The point where the two speech organs make the most contact is named the place of articulation. The way in which the contact forms and then releases is named the manner of articulation.

Let's look at the [p] sound as an example.

To produce the [p] sound, we join our lips together tightly (place of articulation). This causes a slight build-up of air, which is then released when the lips part (manner of articulation), creating a burst of sound associated with the letter P in English.

In English, there are two main sounds we create: consonants and vowels.

Consonants are speech sounds created by the partial or total closure of the vocal tract. In contrast, vowels are speech sounds produced without stricture in the vocal tract (meaning the vocal tract is open and the air can escape without generating a fricative or plosive sound).

Let's take a closer look at the production of consonant and vowel sounds.

Consonants

“A consonant is a speech sound which is pronounced by stopping the air from flowing easily through the mouth, especially by closing the lips or touching the teeth with the tongue”.

(Cambridge Advanced Learner’s Dictionary)

The study of the production of consonant sounds can be divided into three areas: voice, place of articulation, and manner of articulation.

Voice

In articulatory phonetics, voice refers to the presence or absence of vibration of the vocal cords.

There are two types of sound:

- Voiceless sounds - These are made when the air passes through the vocal folds, with no vibration during the production of sounds, like [s] as in sip.

- Voiced sounds - These are made when the air passes through the vocal folds, with vibration during the production of sounds like [z] as in zip.

Practice! - Put your hand on your throat and make the [s] and [z] sounds in succession. Which one produces the vibration?

The place of articulation refers to the point where the construction of airflow takes place.

There are seven different types of sounds based on the place of articulation:

- Bilabial - Sounds produced with both lips, such as [p], [b], [m].

- Labiodentals - Sounds produced with the upper teeth and the lower lip, such as [f] and [v].

- Interdental - Sounds produced with the tongue in between the upper and lower teeth, such as [θ] (the 'th' sound in think).

- Alveolar - Sounds produced with the tongue at or near the ridge right behind upper front teeth, such as [t], [d], [s].

- Palatal - Sounds produced at the hard palate or the roof of the mouth, such as [j], [ʒ] (measure), [ʃ] (should).

- Velars - Sounds produced at the velum or soft palate, such as [k] and [g].

- Glottals - Sounds produced at the glottis or the space between the vocal folds, such as [h] or the glottal stop sound [ʔ] (as in uh-oh).

Manner of Articulation

Manner of articulation examines the arrangement and interaction between the articulators (speech organs) during the production of speech sounds..

In phonetics, speech sounds can be divided into five different types based on the manner of articulation.

- Plosive (aka stops) - sounds made by the obstruction and release of the air stream from the lungs. Plosive sounds are harsh sounds, such as [p, t, k, b, d, g].

- Fricative - sounds formed when two articulators come close but don't touch, forming a small gap in the vocal tract. Since the airflow is obstructed, this small gap generates audible friction, such as [f, v, z, ʃ, θ].

- Affricate sounds - these sounds are the result of plosive and fricative sounds happening in rapid succession. For example, the affricate [tʃ] represents [t] plus [ʃ], just as the affricate [dʒ] results from [d] plus [ʒ]. The first of these is unvoiced and the second is voiced.

- Nasal sounds - produced when the air passes through the nasal cavity instead of out through the mouth, such as [m, n, ŋ].

- Approximant - sounds made with partial obstruction of the airflow from the mouth. This means some sounds are coming out of the nose and some from the mouth, such as [l, ɹ, w, j].

Vowels

“A vowel is a speech sound produced when the breath flows out through the mouth without being blocked by the teeth, tongue, or lips”.

(Cambridge Learner’s Dictionary)

Linguists describe vowel sounds according to three criteria: Height, Backness and Roundness.

Height

Height refers to how high or low the tongue is in the mouth when producing a vowel. For example, consider the vowel sounds, [ɪ] (as in sit) and [a] (as in cat). If you say both of these vowels in succession, you should feel your tongue going up and down.

In terms of height, vowels are either considered: high vowels, mid vowels, or low vowels.

- [ɪ] as in bit is an example of a high vowel.

- [ɛ] as in bed is an example of a mid vowel.

- [ɑ] as in hot is an example of a low vowel.

Backness

Backness focuses on the horizontal movement of the tongue. Consider the two vowels [ɪ] (as in sit) and [u] (as in umbrella) and pronounce them one after the other. Your tongue should be moving forward and backwards.

In terms of backness, vowels are either considered: front vowels, central vowels, or back vowels.

- [i:] as in feel, is an example of a front vowel.

- [ə] as in again, is an example of a central vowel.

- [u:] as in boot, is an example of a back vowel.

Roundedness

Roundedness refers to whether or not the lips are rounded or unrounded when producing the vowel sound. When we pronounce rounded vowels, our lips are open and extended to some degree. An example of a rounded vowel is [ʊ] as in put.

When we pronounce unrounded vowels, our lips are spread and the corners of the mouth are pulled back to some degree. An example of an unrounded vowel is [ɪ] as in bit.

Acoustic phonetics

Acoustic phonetics is:

The study of how speech sounds travel, from the moment they are produced by the speaker until they reach the listener's ear.

Acoustic phonetics looks at the physical properties of sound, including the frequency, intensity, and duration, and analyses how sound is transmitted.

When sound is produced, it creates a sound wave that travels through the acoustic medium (this is usually the air, but it could also be water, wood, metal etc., as sound can travel through anything except a vacuum!). When the sound wave reaches our eardrums, it causes them to vibrate; our auditory system then converts these vibrations into neural impulses. We experience these neural impulses as sound.

Sound wave - A pressure wave that causes particles in the surrounding acoustic medium to vibrate.

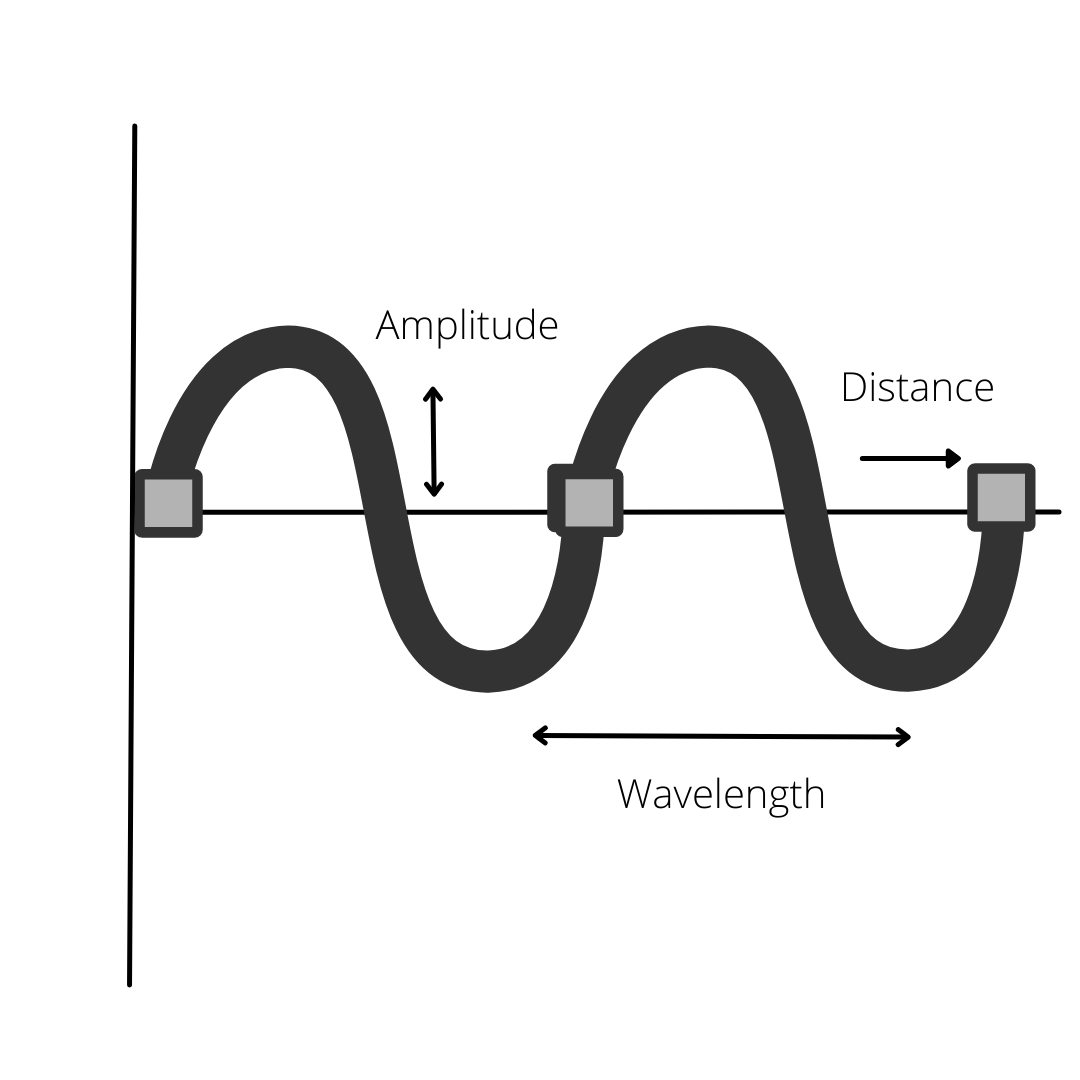

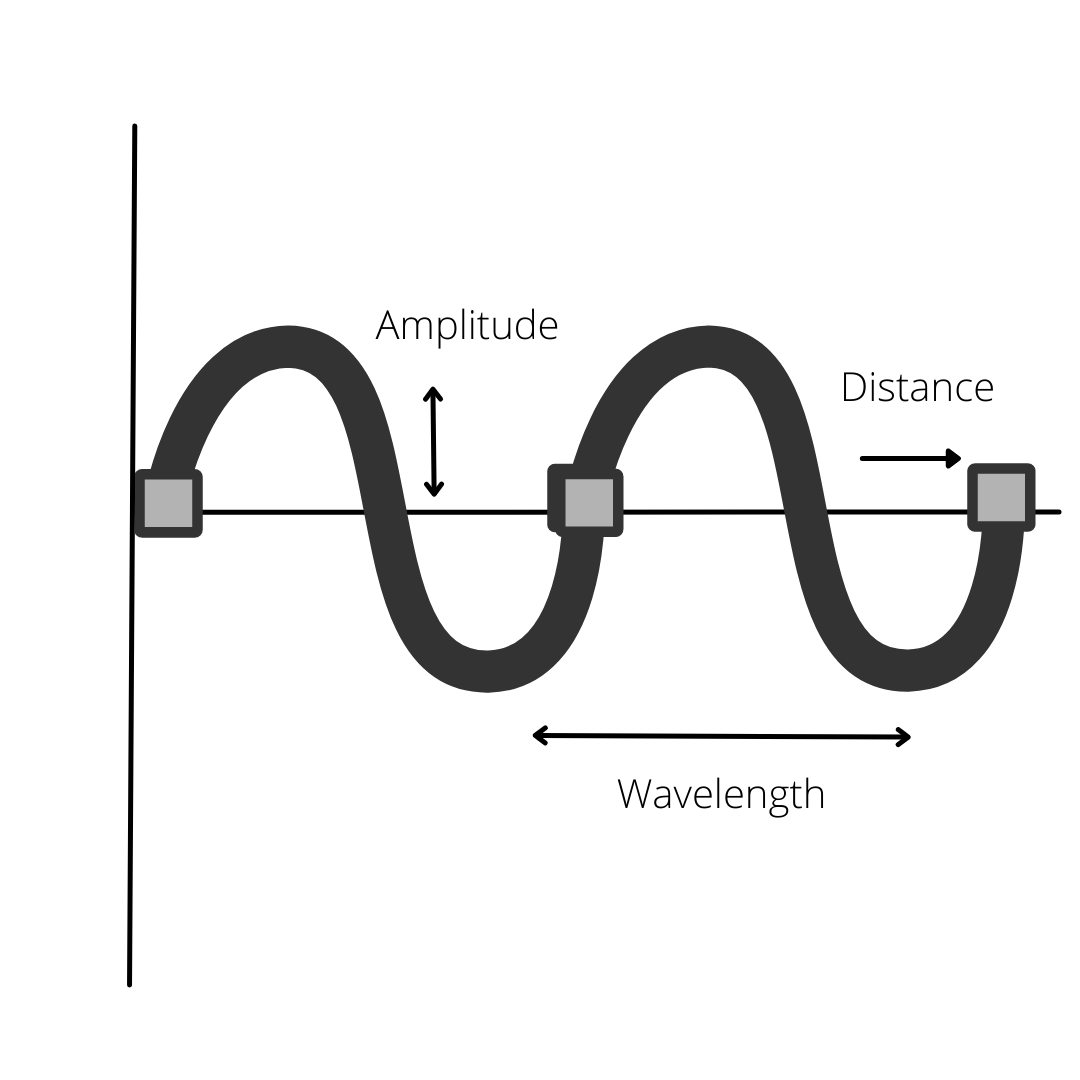

Linguists examine the movement of sound by studying the sound waves that are created during speech. There are four different properties of sound waves: wavelength, period, amplitude, and frequency.

Fig. 1 - A sound wave includes the different properties of amplitude, distance and wavelength.

Wavelength

The wavelength refers to the distance between the crests (highest points) of the sound wave. This indicates the distance the sound travels before it repeats itself.

Period

The period of a sound wave refers to the amount of time it takes for the sound to create a complete wave cycle.

Amplitude

The amplitude of a sound wave is represented in height. When the sound is very loud, the amplitude of the sound wave is high. On the other hand, when the sound is quiet, the amplitude is low.

Frequency

The frequency refers to the number of waves produced per second. In general, low-frequency sounds produce sound waves less often than high-frequency sounds. The frequency of sound waves is measured in Hertz (Hz).

Auditory phonetics

Auditory phonetics is:

The study of how people hear speech sounds. It is concerned with speech perception.

This branch of phonetics studies the reception and response to speech sounds, mediated by the ears, the auditory nerves, and the brain. While the properties of acoustic phonetics are objectively measurable, the auditory sensations examined in auditory phonetics are more subjective and are typically studied by asking listeners to report on their perceptions. Thus, auditory phonetics studies the relationship between speech and the listener's interpretation.

Let's look at the basics of how our auditory and hearing system works.

As sound waves travel through the acoustic medium, they cause the molecules around them to vibrate. When these vibrating molecules reach your ear, they cause the eardrum to vibrate too. This vibration travels from the eardrum to three small bones within the middle ear: the mallet, the incus, and the stirrup.

Fig. 2 - The three small bones in the middle ear are collectively called the ossicles.

Fig. 2 - The three small bones in the middle ear are collectively called the ossicles.

The vibration is carried to the inner ear and into the cochlea via the stirrup.

The cochlea is a small snail shell-shaped chamber within the inner ear, which contains the sensory organ of hearing.

The cochlea converts the vibrations into neural signals which are then transmitted to the brain. It is in the brain where the vibrations are identified as actual sound.

Auditory phonetics can be particularly useful in the medical field as not everyone can easily decipher different sounds. For instance, some people suffer from Auditory Processing Disorder (APD), which is a disconnect between hearing and processing sounds. For example, if you asked a person who suffers from Auditory Processing Disorder, “Can you close the door?”, they may hear something like “Can you doze the poor?” instead, as the disorder makes it more difficult to decipher sounds.

Phonetic sounds and symbols

To transcribe phonetic sounds into symbols, we use the International Phonetic Alphabet.

The International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA) is a system for representing phonetic sounds (phones) with symbols. It helps us transcribe and analyse speech sounds.

The International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA) was developed by the language teacher Paul Passy in 1888 and is a system of phonetic symbols based primarily on Latin script. The chart was initially developed as a way of accurately representing speech sounds.

The IPA aims to represent all qualities of speech and sounds present in language, including phones, phonemes, intonation, gaps between sounds, and syllables. The IPA symbols consist of letter-like symbols, diacritics, or both.

Diacritics = Small symbols added to a phonetic symbol, such as accents or cedillas, that show slight distinctions in sounds and pronunciation.

It is important to note that the IPA is not specific to any particular language and can be used globally to help language learners.

The IPA was created to help describe sounds (phones), not phonemes; however, the chart is often used for phonemic transcription. The IPA itself is big. Therefore, when studying the English language, we would most likely use a phonemic chart (based on the IPA), which only represents the 44 English phonemes.

Fig. 3 - The English phonemic chart contains all of the phonemes used in the English language.

Fig. 3 - The English phonemic chart contains all of the phonemes used in the English language.

Phones vs phonemes -

A phone is a physical sound - when you speak (make a sound) you produce phones. Phones are written between square brackets ( [ ] ).

A phoneme, on the other hand, is the mental representation and meaning we associate with that sound. Phonemes are written between slashes ( / / ).

Transcribing phones

When we describe phones, we use narrow transcription (to include as many aspects of a specific pronunciation as possible) and place the letters and symbols between two square brackets ( [ ] ). Phonetic (narrow) transcriptions give us lots of information about how to physically produce sounds.

For example, the word 'port' has an audible exhalation of air after the letter 'p'. This is shown in the phonetic transcription with a [ʰ] and the word port in phonetic transcript would look like this [pʰɔˑt].

Let's take a look at some more examples of phonetic transcription.

- Head - [ˈhɛd]

- Shoulders- [ˈʃəʊldəz]

- Knees - [ˈniːz]

- And - [ˈənd]

- Toes - [ˈtəʊz]

Transcribing phonemes

When describing phonemes, we use broad transcription (only mentioning the most notable and necessary sounds) and place the letters and symbols between two slashes ( / / ). For example, the English word apple would look like this /æpəl/.

Here are some further examples of phonemic transcriptions

- Head - / hɛd /

- Shoulders - / ˈʃəʊldəz /

- Knees - / niːz /

- And - / ənd /

- Toes - / təʊz /

As you can see, both transcriptions are very similar, as they follow the IPA. However, look closely, and you will see some diacritics in the phonetic transcriptions that do not appear in the phonemic transcriptions. These diacritics provide a few more details about how to pronounce the actual sounds.

These transcriptions all follow British English pronunciation.

Why do we need the International Phonetic Alphabet?

In English, the same letters in a word can represent different sounds, or have no sound at all. Therefore, the spelling of a word is not always a reliable representation of how to pronounce it. The IPA shows the letters in a word as sound-symbols, allowing us to write a word as it sounds, rather than as it is spelt. For example, tulip becomes /ˈtjuːlɪp/.

The IPA is very helpful when studying a second language. It can help learners understand how to pronounce words correctly, even when the new language uses a different alphabet to their native language.

Phonetics - Key takeaways

- Phonetics is the branch of linguistics that deals with the physical production and reception of sounds.

- Phonetics studies speech from different viewpoints and is broken down into three categories: Articulatory phonetics, Acoustic phonetics, and Auditory phonetics.

- Articulatory phonetics is concerned with the way speech sounds are created and aims to explain how we move our speech organs (articulators) to produce certain sounds.

- Acoustic phonetics is the study of the way speech sounds travel, from the moment they are produced by the speaker until they reach the listener's ear.

- Auditory phonetics studies the reception and response to speech sounds, mediated by the ears, the auditory nerves, and the brain.

- The International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA) is a system for representing phonetic sounds (phones) with symbols. It helps us pronounce words correctly.

References

- Fig. 2. Cancer Research UK, CC BY-SA 4.0 , via Wikimedia Commons

- Fig. 3. Snow white1991, CC BY-SA 3.0 , via Wikimedia Commons

Similar topics in English

Related topics to Phonetics