The Byzantine period

Constantine I took over the Roman Empire after he won the Battle of the Milvian Bridge in October 312 A.D. His victory brought an end to the system of Tetrarchy. As a result, Constantine I became the sole emperor of the Empire.

Tetrarchy

A ruling system established by Emperor Diocletian in 293. Under the system, four Emperors would rule the Empire. Two were seniors and called augusti and two were their juniors and successors called caesares.

This battle also marked the beginning of his conversion to Christianity, which would later become the Empire’s official religion. Lactantius and other advisors of the Emperor alleged that Constantine had a vision from the Christian God during the battle, after which he attributed his win to Him. Indeed, Constantine was baptised shortly before his death in 337 A.D.

In 330 A.D., Constantine I established Constantinople as the capital of the Byzantine Empire.

Constantinople was a melting pot of different cultures ranging from Slavic, western European, and Asian. The official language was Latin, but Greek was also widely spoken.

Social mobility was relatively possible, which suggests that the Byzantine Empire was not so class-restricted as other empires of its time. Ultimately, the Byzantine Empire spanned much of the present-day Mediterranean, including Greece, Italy, Turkey, and portions of North Africa and the Middle East.

Byzantine definition

As we said, Constantine I established Constantinople as the capital of the Byzantine Empire in 330. His intention was to found a new Rome. As a result, the people of the Byzantine Empire called themselves Romans rather than Byzantines.

Byzantium was, actually, a Greek colony established by Byzas where Constantinople (Istanbul today) was located.

In other words, the name Byzantium is anachronistic. It was used by historians to differentiate the East Roman Empire from the Western Roman Empire, but its people never thought of themselves as Byzantines.

Anachronistic

Belonging to a different period than is portrayed.

Division after Constantine I

Constantine I died in 337 AD. After his death, the Empire fragmented. His successor, Emperor Valentinian I, divided the Empire again into a Western part, which he ruled, and an Eastern part ruled by his brother Valens. Nonetheless, the West was much more vulnerable than the East. The constant attacks by the Visigoths and other Germanic tribes led to an increasing loss of territory in the West. By 476, the barbarian Odoacer overthrew the child Emperor Romulus Augustulus and named himself King of Italy. By that point, Italy was the last territory still controlled by the Western Roman Empire. This event marked the end of the Western Roman Empire.

Barbarian

Name given to all the people that were not from the Byzantine Empire. This implied they were perceived as inferior and less civilised.

The Golden Age of the Byzantine Empire

Let’s explore the Byzantine Empire’s days of glory, which started in 527 with the rule of Justinian I.

Justinian I

Justinian I took over the Empire in 527 from his uncle Justin I. During his reign until 565, the Byzantine Empire experienced a Golden Age in which Justinian enacted a renovatio imperii.

Renovatio imperii

Latin for ‘Renovation of the Empire’. It encapsulated Justinian I’s reforms in the legal, civil, and military departments which aimed at strengthening the Byzantine Empire.

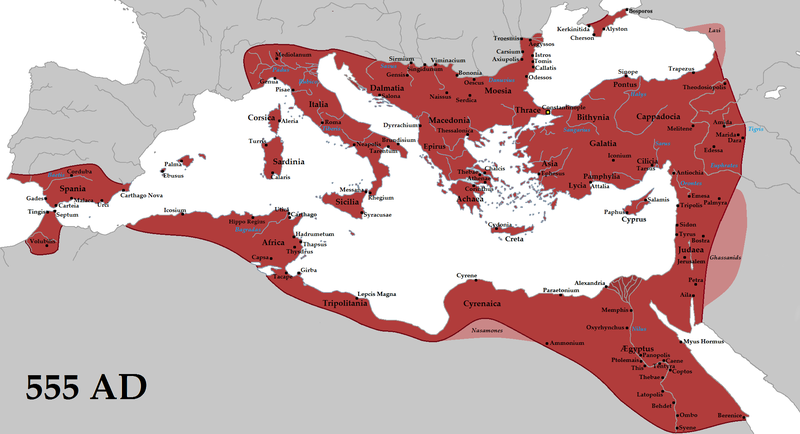

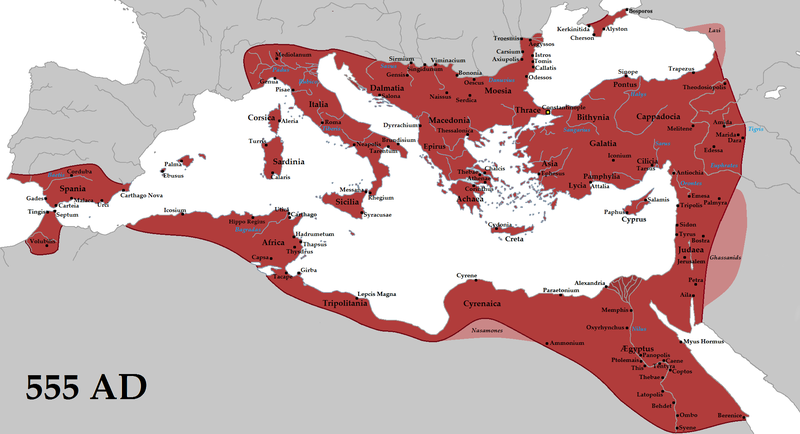

The lands of the Empire reached their height during this period and came to span parts of the former Western Empire all the way to the Middle East and Anatolia.

In 540, after a successful siege of Naples and Rome by military commander Flavius Belisarius, Justinian took back Rome and the Kingdom of Italy from the barbarians. In 548, Belisarius also retook Africa Proconsularis from the Vandals. This was a small Roman province in North Africa comprising parts of modern-day Tunisia, Algeria, Libya, and the Gulf of Sirte.

In the East, the Roman-Persian Wars continued until 561, when the envoys of Justinian and the Persian Emperor Khosrau agreed on a 50-year peace deal. By the end of his reign, the Byzantine Empire was the most powerful in the world.

Byzantine Empire Map

Fig. 1: Map depicting the extent of the Byzantine Empire in 555 AD

Byzantine Empire Flag

Fig. 2: Byzantine imperial ensign, according to Pietro Vesconte's portolan chart.

Nika riots

Justinian’s reign was not peaceful from the start. In 532, just five years into his rule, Constantinople experienced the most violent riots in its history and half of it was burnt down. These were the Nika (‘victory’) riots. The Greens and the Blues, two chariot racing factions, initiated the riots. At the time, the chariot races were a place where people made political demands, and the two factions acted as informal political parties. However, both the Greens and the Blues were dissatisfied with Justinian’s reduction of their power and thus initiated the riots.

Fig 3: Hagia Sophia in Istanbul.

Fig 3: Hagia Sophia in Istanbul.

Justinian had to call in his troops and it took them weeks to suppress the riots. 30 rioters were killed. Justinian I wanted to restore his image after the bloodbath and decided to build, at the site of a destroyed church, a grand Cathedral, which he called Hagia Sophia (‘Holy Wisdom’).

The historians Helen Gardner and Fred Kleiner wrote that the dimensions of Hagia Sophia are impressive considering that it’s not made of steel. The Cathedral was 83 metres long and 73 metres wide, with its crown rising 53 metres above the ground. It was completed in 537 and it became a symbol of prestige for the Christian faith. The cathedral also added to Justinian’s own prestige as it implied he was building a grand Empire.

This allowed him to consolidate his imperial power.

The Justinian Code

In 529, the Emperor appointed a ten-man commission chaired by John the Cappadocian to revise Roman law. The main issue with the Roman law the Byzantine Empire had inherited was that it was not uniform, and different regions had different legal practices.

The men created the Corpus Juris Civilis (body of civil law) or Justinian Code, which unified the different legal practices under one system. In 534 the Corpus was updated to take account of Justinian’s Novellae Constitutiones (new constitutions), which were mostly written in Greek.

This made the laws widely accessible (as Greek was the main language spoken) and fairer as they were standardised across the Empire.

Did you know?

The Corpus is the foundation of civil law in most modern European states!

The fall of the Byzantine Empire

Despite the apparent prosperity of the Empire under Justinian I and his successors all the way up to the tenth century, its fortunes took an unsavoury turn in the eleventh century. The continuous civil strife, alliances gone awry, and the rise of the Seljuk Empire led to the fall of the Byzantine Empire by 1453.

Civil wars

The single most important factor in the collapse of the Byzantine Empire was its debilitating cycles of internal strife, which gradually led to a collapse in the power and national unity of the Empire. Between 1071-81 there were eight civil wars.

The most important of these uprisings was that of Georgi Voyteh, which was initiated in the Bulgarian province in 1072. The reason for the uprising was the perceived weakness of the Empire after its defeat at the Battle of Manzikert in 1071, which encouraged the province to seek independence. The revolt was not suppressed until 1073 when commander Nikephoros Bryennios successfully invaded the province.

This uprising was a turning point in the prosperity of the Empire. The perception had radically shifted from the Golden Age of Justinian I, and now the provinces felt they could feasibly defeat the Emperor. This perceived weakness led to a series of attempts to usurp the throne, the last of which was by Alexios I Komnenos in 1081, which was successful. He was in power until 1118.

The Empire experienced some stability under the Komnenos dynasty, which also saw the victory of the First Crusade in 1095–99, but a second wave of civil strife began after Manuel I Komnenos’ death in 1180. His son Alexios II Komnenos was overthrown by his nephew Andronikos I Komnenos. Andronikos’ reign of terror, which lasted until his death in 1185, severely destabilised the Empire and led to further loss of territory.

The Angelos dynasty ruled after the Komnenos dynasty until 1204. During this period, Bulgaria and Serbia successfully claimed independence and further lands were lost to the Seljuk Turks.

In 1203, the imprisoned and deposed Emperor Alexios IV Angelos escaped to the West, where he conspired with the crusaders. He promised them riches and a West-aligned Byzantine Empire, but these promises were impossible to keep.

Ultimately, the impotence and the constant in-fighting of the Angelid dynasty was a major factor in the sack of Constantinople in 1204 and the fall of the Byzantine Empire to the Latin Church.

Rise of the Seljuk Turks: the Battle of Manzikert 1071

The Seljuk Empire had been prominent since the 1030s, but their first major breakthrough against the Byzantine Empire was at the Battle of Manzikert in 1071. During the battle, Emperor Romanos IV Diogenes was captured by the Seljuk leader, Alp Arslan. This fact diminished the prestige of the Byzantine Emperor. During the battle, many mercenaries deserted and fled, leaving the native tagmata to bear the brunt of the Seljuk attack.

Mercenaries

Professional soldiers hired to serve in foreign armies.

The defeat led to further internal deterioration and economic problems. Notably, it started another civil war that lasted from 1073–74. The Byzantines had practically lost Anatolia, which began to be Turkified. By 1080, the Seljuk Empire in Anatolia had gained an area equivalent to 78,000 square kilometres. This led to mass Turkic migration in the region.

The loss of respect for the Byzantine Emperor amongst his subjects was most prominently seen in 1072, a year after the defeat at Manzikert, when the Bulgarian province instigated the revolt of independence.

The wars with the Turkic Empires continued for centuries and Constantinople eventually fell to the Ottoman Empire and Mehmet II in 1453. After this, the Byzantine Empire was lost forever.

Fourth Crusade

The Fourth Crusade lasted from 1202–04. The aim of the crusade was to retake Jerusalem from the Seljuk Empire, but the crusaders eventually targeted Constantinople instead. This led to the sack of Constantinople in 1204 after which the Byzantine Empire was partitioned between the Republic of Venice and the crusader army led by Boniface I.

The partition created a new Latin Empire under Baldwin I. Successor Byzantine states were set up in Nicaea, Trebizond, and Epirus, which managed to reclaim Constantinople in 1261. Nonetheless, the loss of the capital had been a fatal blow for the Empire. With unity diminished, a series of civil wars broke out in 1321–28 and 1341–47, which completely broke the little power that was left in the Empire. This led to the Fall of Gallipoli to the Ottoman Empire in 1354. The Byzantines lost all their possessions in Anatolia apart from Philadelphia.

Byzantine Empire - Key takeaways

- The Byzantine Empire was founded by Constantine I after he came out victorious in the Battle of the Milvian Bridge in 312.

- The Empire lived its Golden Age during the reign of Justinian I. He created the Hagia Sophia and conquered lands from the former Western Roman Empire all the way to the Middle East.

- The Justinian Code standardised the different legal practices across the provinces of the empire, leading to a much more comprehensive legal system.

- The Byzantine Empire started fragmenting in the eleventh century. The main reasons for its collapse by 1453 were the continuous internal strife, the antagonism with the Latin Church, and the rise of the Seljuk Empire.

References

- Fig. 1: Justinian555AD (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Justinian555AD.png) by Tataryn (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/User:Tataryn) is licensed by CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)

- Fig. 2: Byzantine imperial flag, 14th century according to Pietro Vesconte (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Byzantine_imperial_flag,_14th_century_according_to_Pietro_Vesconte.png) by Dragovit (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/User:Dragovit) is licensed by CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)

- Fig. 3: Hagia Sophia Mars 2013 (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Hagia_Sophia_Mars_2013.jpg) by Arild Vågen (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/User:ArildV) is licensed by CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0).

Similar topics in History

Related topics to The Crusades