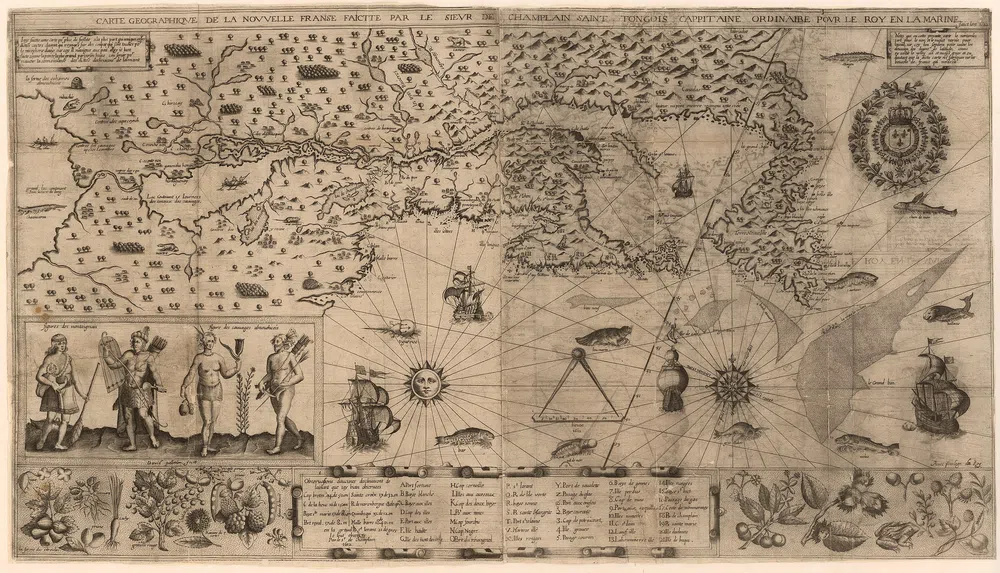

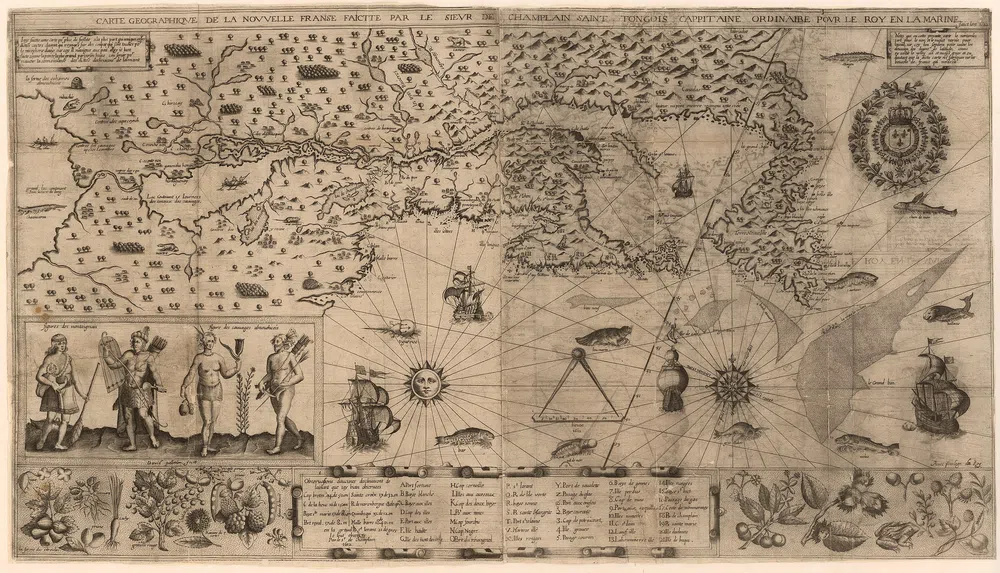

Fig. 1 - Map of New France, by Samuel de Champlain, 1612.

Summary of the French Colonization

Before the French, the Spanish and the British established their first colonies in North America in present-day Florida and Virginia in the latter part of the 16th century, respectively. In contrast, the French did not set up their first settlements until the early 17th century in present-day Canada, with Port-Royal (Annapolis Royal) in 1605 and Quebec in 1608. These North American colonies joined the French empire, which comprised parts of the Caribbean.

- The French colonies in North America were called New France (Nouvelle France or Gallia Nova) (1534-1763). This term refers to the territory of North America, which spanned from Hudson’s Bay in the north to the Gulf of Mexico in the south. New France also comprised the territory from Newfoundland in the northeast to the Canadian prairies in the geographic center of the continent. It included the Great Lakes region and parts of the trans-Appalachian west. Some historic cities linked to French colonization are Quebec, Canada, and New Orleans, U.S.

- In its heyday in the early 1700s, French colonists maintained five administrative regions to govern New France:

- Canada,

- Acadia (Nova Scotia),

- Louisiana,

- Plaisance (Newfoundland),

- Hudson’s Bay.

Italian explorer Giovanni da Verrazzano working for King Francis I of France, was the first to use the term “New France” in 1529. Five years later, the King tasked another navigator, Jacques Cartier, with exploring the continent’s northeast, specifically Newfoundland and the St. Lawrence River. It was then that Cartier claimed the Gulf of St. Lawrence for his king.

Did you know?

Canada was the most extensively developed region comprising Trois-Rivières, Montreal, and Quebec.

Fig. 2 - Giovanni da Verrazano by Francesco Allegrini and Giuseppe Zocchi, 1767.

French Colonial Empire

Over time, the French established colonies in the Americas, Asia, Africa, and Oceania.

Countries Colonized by the French

France had a vast colonial empire between the early 16th and mid-20th centuries. Some of its colonies include:

| Continent | Locations |

| Americas | - Canada (including Quebec, parts of Ontario, parts of Manitoba, Newfoundland, and Hudson's Bay)

- U.S. (Louisiana territory)

- Mexico

- Brazil

- Chile

- Argentina

- Several Caribbean islands (Haiti, Trinidad and Tobago, Saint Lucia, et al.)

- and others

|

| Africa | - Egypt

- Algeria

- Morocco

- Tunisia

- Ivory Coast

- Nigeria

- Chad

- Mali

- Cameroon

- Gabon

- and others

|

| Asia | - Laos

- Cambodia

- Vietnam

- Parts of China

- Parts of India

- and others

|

| Middle East | - Syria mandate

- Lebanon mandate

|

| Australia and Oceania | - Polynesia

- Papua New Guinea

- and others

|

Canada

Established in 1608 by the explorer Samuel de Champlain, Quebec became the main settlement of New France and, initially, it's capital. Champlain worked in the fur trade, a significant industry for many settlers except the Catholic missionaries. The region’s harsh climate did not favor traditional farming activities. It was also partly responsible for the 65% return to France of Quebec settlers, as was the initial lack of incentives from the French government. By 1627, however, the French minister Cardinal Richelieu established the Company of New France (the Company of the Hundred Associates). The Company controlled the fur trade in the St. Lawrence Valley in exchange for 200 to 300 annual settlers sent from France.

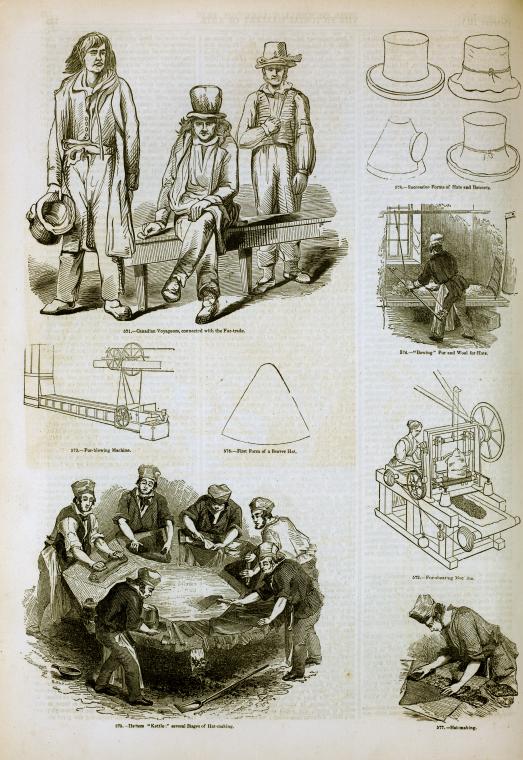

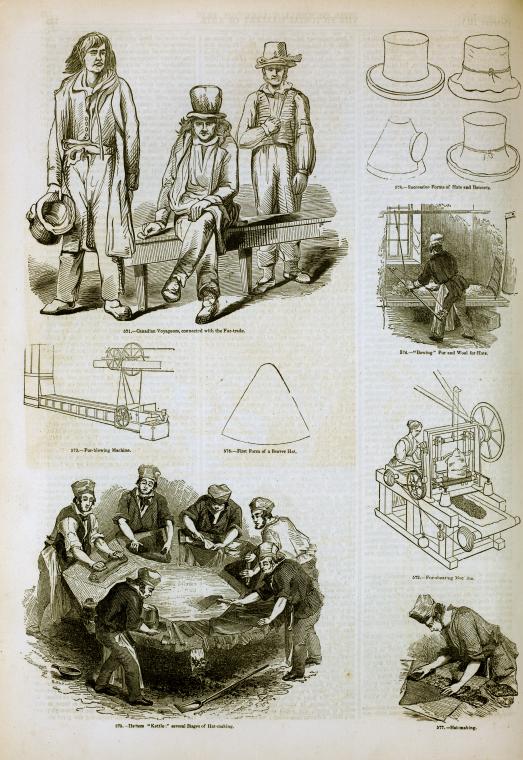

One of the main aspects of Canada’s fur-trade economy was beaver pelts. A pelt is treated animal skin with fur. In Europe, a change in fashion made beaver fur extremely popular, and they were used for such items as fur hats. The Hudson’s Bay Company, then run by Britain, even established the Made Beaver currency to create a price standard and exchange pelts for tokens. France fought to have a stake in the fur trade against its British rival.

For instance, the French explorer and fur trader Pierre Gaultier de Varennes et de La Vérendrye sent 30,000 beaver pelts to Quebec yearly.

This industry was not only a battlefield of commercial competition but also played a significant role in developing a relationship between the indigenous people and the European settlers.

Fig. 3 - Charles Knight's Pictorial Gallery of the Arts, Canadian fur industry, England, 1858.

Another central player in New France was the Catholic Church.

- The Catholic Church, a powerful religious institution, aided the settlers and engaged in the conversions of the indigenous people. The Catholic Récollet Order landed in Quebec in 1615, followed by the Jesuits in 1625. However, this mission is typically described as less aggressive than its counterpart in Central and South America under colonial Spain. The overall relationship between the French settlers and the local tribes was complex. For instance, Champlain sided with the Algonquins and Hurons in a conflict against the Iroquois in 1609.

Eventually, New France expanded westward in search of a passage to the west coast by such explorers as Pierre Gaultier de Varennes et de La Vérendrye. The latter passed through today’s southern Manitoba in 1738 and present-day Pierre, South Dakota in 1743 on the way back, claiming it for France. The French, therefore, became the first Europeans to expand their control of the continent into the Canadian prairies.

Louisiana

The exploration of the Mississippi River by several navigators, such as René-Robert Cavelier Sieur de La Salle, led to the acquisition of Louisiana—an essential part of New France in the southeast of the continent.

Did you know?

Louisiana was named after King Louis XIV, nicknamed the Sun King.

The original French settlers of the area were primarily from Canada rather than France. New Orleans eventually became the capital of Louisiana. As with Quebec, the Catholic Church was a central institution in the area, and its missionary work also targeted the indigenous population.

- Slavery also played a vital role in the Louisiana economy, such as developing plantations in the farming economy. As a result, the French brought thousands of slaves from Africa in the first half of the 18th century. Slavery also existed in other parts of New France. However, in Quebec, its primary purpose was to display social status. In general, the French brought slaves to New France from their colonies in the Caribbean or directly from Africa.

Fig 4 - Map of New France, by Herman Moll, 1732.

Consequences of French Colonization

At this time, Britain and France were rivals for economic and territorial control of the fur trade. Sometimes, their competition led to military conflicts.

For instance, Britain captured Quebec in 1629.

Although the Treaty of Saint-Germain (1632) released Quebec back to New France, conflicts like this undermined France’s colonialism in North America. European wars, such as the War of the Grand Alliance (1689–1697), also extended into the New World as King William’s War. The French successfully defended Quebec in this particular conflict but lost Acadia (Nova Scotia) in 1690.

In other words, the competition for resources and land, as well as military conflicts, contributed to the decline of France’s control of its territory in North America (1763). The British and then the Americans gradually obtained what was once New France.

- The immediate catalyst for its decline was the French and Indian War (1754–1763)—another military conflict linked to the Seven Years' War (1756-1763) in Europe. France fought Britain, each side supported by various indigenous tribes, over the upper Ohio River Valley. The conflict resulted in the Treaty of Paris (1763), which granted Britain the now-former French land east of the Mississippi River, excluding New Orleans and the small islands of St. Pierre and Miquelon next to Newfoundland.

Louisiana bounced between Spain and France and was finally obtained by the newly emergent United States in 1803 in the well-known Louisiana Purchase. The colonial rivalry between major European empires and the new statehoods of the United States (1776) and Canada (1867) also led to ethnic and religious tensions throughout the continent for generations to come. Not only did these tensions involve the poor treatment of the indigenous people, but they also affected the settlers themselves.

For example, 60,000 French found themselves as British subjects in what was to become the Canadian state. Nor was the decline of New France the end of French colonialism.

Aftermath: French Colonization of Africa

France may have lost its North American empire, but from the middle of the 19th century, it expanded into the continent of Africa. Despite the somewhat different historic circumstances, historians consider the French expansion into Africa part of the same colonialist, imperialist framework.

The French colonization of Africa comprised such present-day countries as:

- Cameroon,

- Senegal, Tunisia,

- Ivory Coast,

- the Republic of Congo,

- the Central African Republic,

- Niger,

- Chad,

At this time, other European powers were aggressively colonizing Africa as well.

For example, the Berlin Conference of 1884–1885 involved more than a dozen European powers and regulated the colonization of the African continent.

![French Colonization, Wells Missionary Map Co. Africa. [?, 1908] Map, StudySmarter.](https://s3.eu-central-1.amazonaws.com/studysmarter-mediafiles/media/1865576/summary_images/1865576/summary_images/africa_map_1908_EomJMHw.webp?X-Amz-Algorithm=AWS4-HMAC-SHA256&X-Amz-Credential=AKIA4OLDUDE42UZHAIET%2F20260211%2Feu-central-1%2Fs3%2Faws4_request&X-Amz-Date=20260211T103540Z&X-Amz-Expires=604800&X-Amz-SignedHeaders=host&X-Amz-Signature=4f007f97a6768c0b9ebbb05b1d84045c8d45e51325248cd8fecf45ba3bedc0e8)

Fig. 5 - Wells Missionary Map Co. Africa. [?, 1908] Map.

French Colonization - Key Takeaways

- Between the 16th and mid-20th centuries, France colonized parts of North America, Asia, Africa, and beyond.

- It's North American colonial empire includes parts of present-day Canada in the east and the prairies as well as the large Louisiana territory, most of which was lost in 1763, first to Britain and then to the United States.

- Like other Europeans, French colonialism featured territorial expansion and settlements, missionary work, the control of trade routes and raw materials, and the scientific exploration of new places.

References

- Fig. 4 - Map of New France, by Herman Moll, 1732 (https://www.loc.gov/resource/g3300.ct000677/) digitized by the Library of Congress Geography and Map Division, published before 1922 U.S. copyright protection.

- Fig. 5 - “Africa,” by Wells Missionary Map Co., 1908 (https://www.loc.gov/item/87692282/) digitized by the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, no known restrictions on publication.

![French Colonization, Wells Missionary Map Co. Africa. [?, 1908] Map, StudySmarter.](https://s3.eu-central-1.amazonaws.com/studysmarter-mediafiles/media/1865576/summary_images/1865576/summary_images/africa_map_1908_EomJMHw.webp?X-Amz-Algorithm=AWS4-HMAC-SHA256&X-Amz-Credential=AKIA4OLDUDE42UZHAIET%2F20260211%2Feu-central-1%2Fs3%2Faws4_request&X-Amz-Date=20260211T103540Z&X-Amz-Expires=604800&X-Amz-SignedHeaders=host&X-Amz-Signature=4f007f97a6768c0b9ebbb05b1d84045c8d45e51325248cd8fecf45ba3bedc0e8)