Exploring LGBTQ+ Artwork

You can buy your ticket at the entrance.

Standard fee: Interest.

Reduced fee: Curiosity.

Free entry: Desire to know more.

What defines LGBTQ+ artwork? Similar to LGBTQ+ books and TV shows, LGBTQ+ artwork has queer representation at its core. It openly depicts queerness, contributes to the fight for equal rights, and/or is created by LGBTQ+ artists. It explores matters (and conflicts) of queer identity and social (in)justice, and it often provokes and promotes activism and sparks debate.

Now, art is a very vague term: Is it visual art I’m talking about? Performance art? Something totally different? The fact is that there are thousands upon thousands of art pieces fitting the broad spectrum of LGBTQ+ art, but today in our museum tour, we’re focusing on visual art, i.e. paintings, photography, and some films.

Ground Floor: LGBTQ Art History

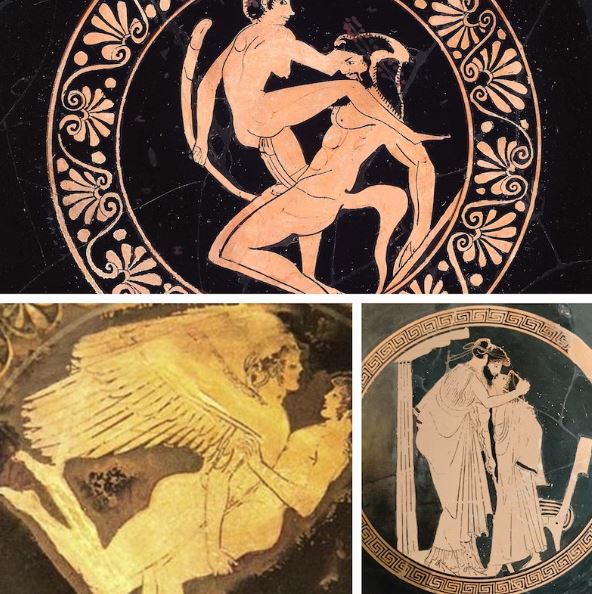

Queer art is by no means something new. Ancient Greeks and subsequent Romans were perfectly fine with pursuing and praising homosexual relationships and gladly depicted them in their visual art. I mean, Zeus was pretty liberal with his choices of sexual encounters, so he definitely graced some Greek vases, along with depictions of other gods.

Corner to Your Left: First LGBTQ Art

As it usually happens, it’s difficult to pinpoint the first piece of queer art. After all, history devours its children too. Still, let’s not beat around the bush and take a look at those Greek vases.

I’m not gonna lie; Greeks were fairly explicit.

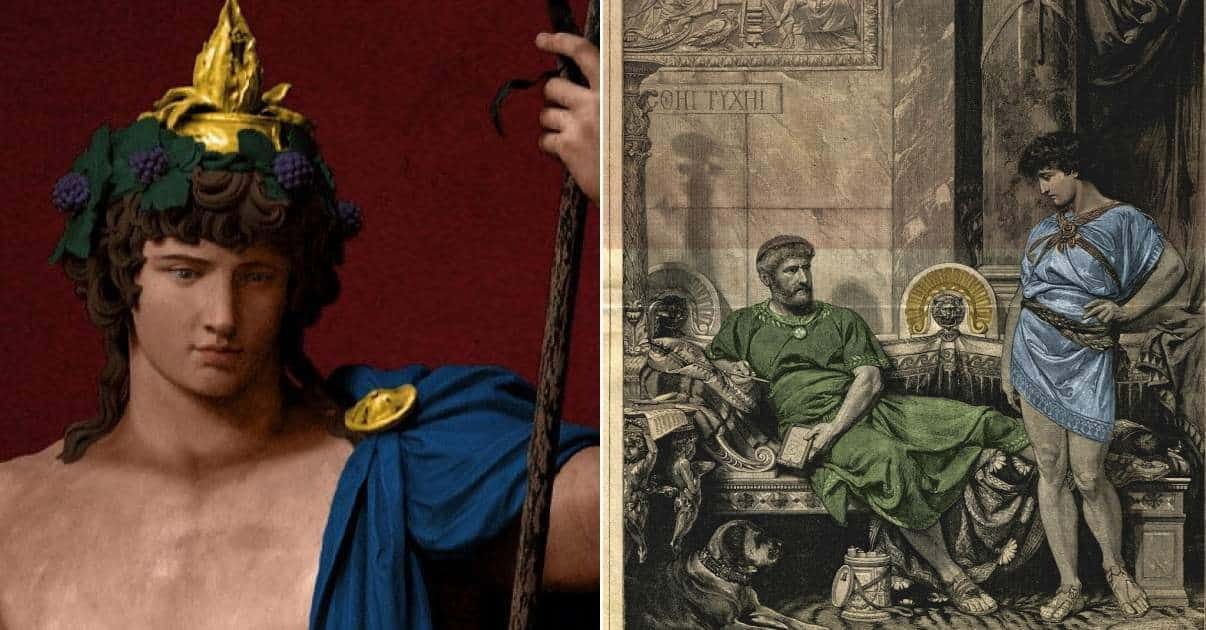

Across the hall, in the right corner, you can see Roman queer art too. Just like Greeks, Romans thought homosexuality was normal and natural and even encouraged it among young men as a rite of passage. Many Roman emperors were bisexual, but Hadrian was probably the first to openly declare his homosexuality and devote his life to his lover, Antinous. The painting shows the two at court, and although it’s not as explicit as Greek art, we all know what’s going on there!

While we’re here, you can look at Paul Gauguin’s 1902 painting The Sorcerer of Hiva Oa, which defies binary gender norms. Those French modernists knew their stuff, didn’t they?

Central Hall: Early Queer-Coded Art

As you know, admitting one’s homosexuality was a free pass into the nearest prison back in the day. However, that did not mean people didn’t pursue same-sex relationships – they only had to be clever about it. Over time, various codes were invented to refer to queerness in day-to-day life and in art itself. While metropoles like Berlin, Paris, and Harlem became more open and welcoming to LGBTQ+ people, the rest of the world wasn’t so quick on the uptake. Artists found ways of self-actualisation through art, which played only a part in greater identity politics.

You’d be surprised to find that pulp fiction magazines were among the first to display homosexual relationships on their mass-produced paperbacks in the 1950s and 1960s. Although the covers often featured exaggerated poses, seductive looks, and nudity, they were among the first affordable means for people to get acquainted with homosexuality. The titles of these novels were often coded: words such as twilight and strange indicated lesbian content, and themes of racism and prostitution hinted at gay relationships.

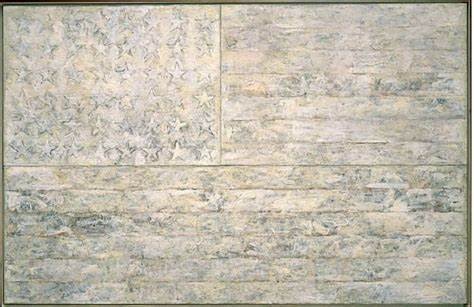

On the more academic side of art, queer-coded imagery was displayed through monochromatic imagery. For instance, Jasper Johns’s famous painting White Flag (1955) is an example of coded art. The painting shows the bleached American flag and represents the repression and isolation queer people (for Johns, gay men in particular) feel in the US.

Agnes Martin’s painting The Night Sea (1963) shows her experience as a closeted lesbian. Not only does she display the sea in a perfectly measured square, but the sea is also divided into equal sections. If you’ve ever seen a sea, even in cartoons, you’ll know it’s impossible to make it linear and organised – you may as well go mad trying. The queer community conveyed the sense of dispossession and not belonging in a world that forces people into perfect boxes, suppressing their identities.

If you go into the small room next to the stairs, you can take a look at one of Rosa von Praunheim’s films. Due to the Hollywood Production Code, which prohibited displays of homosexuality, many people felt compelled to hide their identities. Von Praunheim was one of the pioneers of queer movies and has directed over a hundred since the 1960s. Nowadays, there are many great films, all of which owe Rosa von Praunheim a debt of gratitude.

Stairs: The Memorial Walk

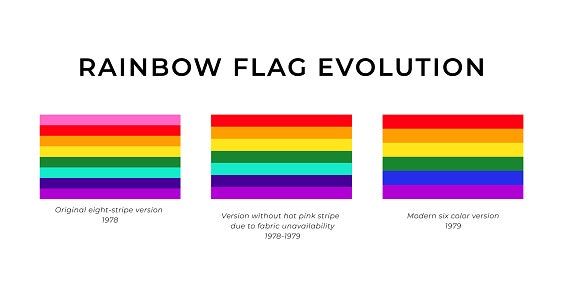

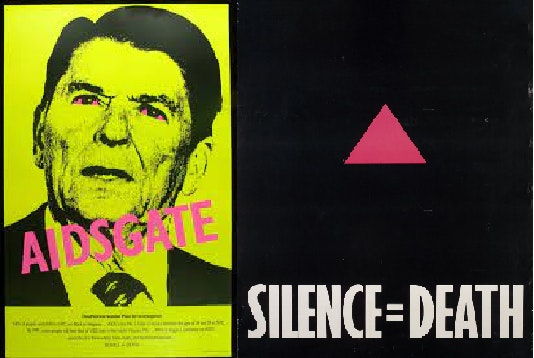

As you walk through the museum of LGBTQ+ art, you are asked to remember everyone who has suffered for simply being themselves. Another symbol that played an important role in encoding queerness was the pink triangle. The symbol was used in concentration camps to mark homosexuals brutally tortured and murdered during WWII. The pink triangle was appropriated by the LGBTQ+ community and used in the early years of the gay liberation movement, but due to its heavy connotation, it was later replaced by the iconic Rainbow Flag.

First Floor: LGBTQ+ Art After Stonewall

The Stonewall Riots changed everything in 1969. Sparked by a violent police raid on a popular gay bar, The Stonewall Inn, the world was called to arms in the fight for LGBTQ+ rights. The first Pride was held in 1970 in several large cities in the USA. Gilbert Baker created the Rainbow Flag to symbolise the LGBTQ+ movement. Its colours stand for acceptance and inclusion.

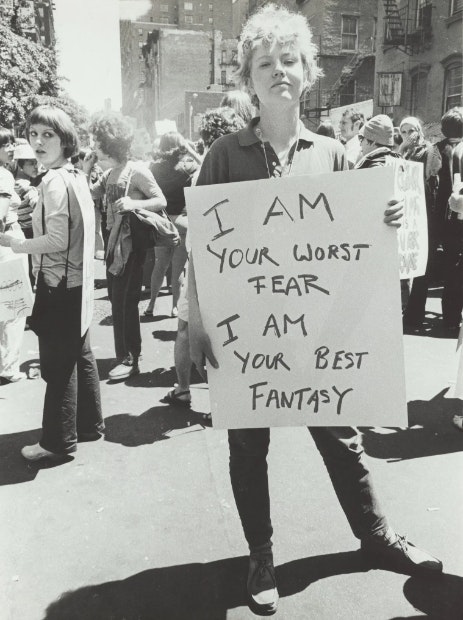

Photography entered the art sphere, especially around the time when the first Pride happened. Multiple images provoked action and invited the LGBTQ+ community to fight on. For example, Donna Gottschalk, one of the prime queer photographers, is captured on camera by Diana Davies at Pride. The sign she’s holding indicates both fear and fascination surrounding the LGBTQ+ community in the 1970s.

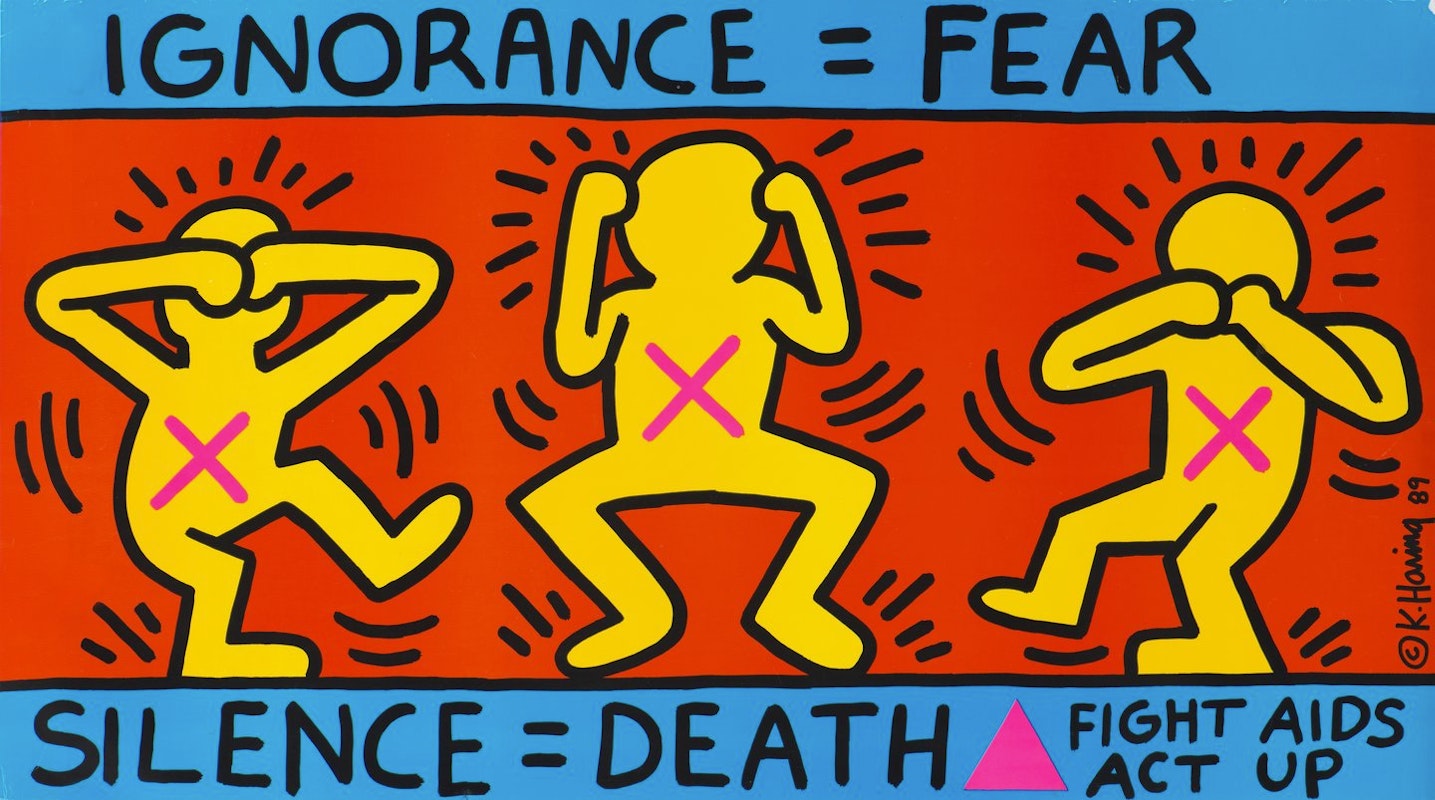

With the rise of the HIV/AIDS epidemic that hit the LGBTQ+ community heavily, the so-called Lavender Scare gained momentum. Namely, it was misconstrued that homosexuals were solely responsible for spreading the virus. Many medical specialists refused to treat homosexuals, and the gutter press stoked the fear surrounding AIDS in ways that stigmatised the LGBTQ+ community. The Silence=Death Project was started to raise awareness about the imminent dangers of closing one’s homophobic eyes to the alarming issue.

Keith Haring, one of the most resilient fighters at the forefront of the movement, created a pop art piece, Ignorance = Fear / Silence = Death, in 1989 to bring attention to the problem. Alongside it, you can see a few other activist paintings of the movement.

Left Wing: Famous LGBTQ+ Art

Some of the most famous pieces of LGBTQ+ art are displayed here. While you’re looking around, remember that queer art was always political and might continue to be for the foreseeable future. It was necessary to make a statement to be listened to. How much of it was heard remains a matter of discussion.

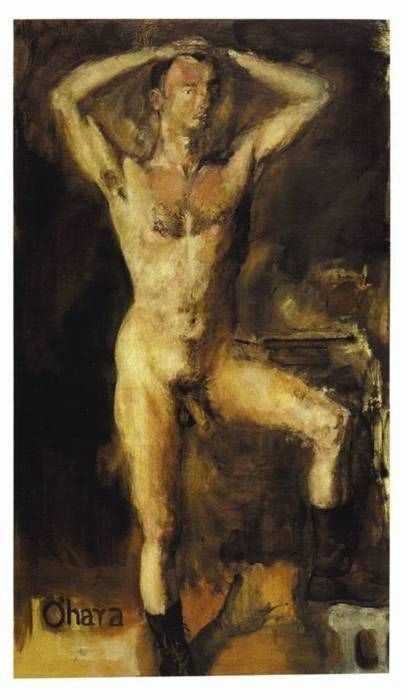

Portraits were among those queer-coded artworks, and Larry Rivers used to make multitudes of them. O’Hara Nude with Boots was one of the most provocative portraits of O’Hara, which signalled the shift in visual arts (1954).

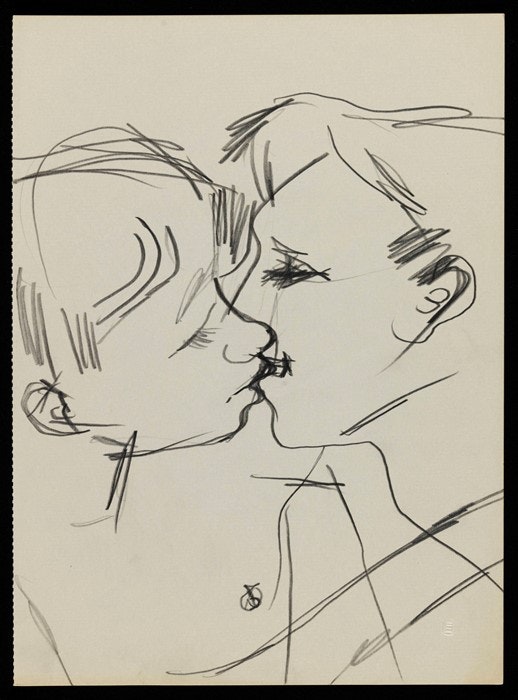

Drawing of Two Men Kissing by Keith Vaughan illustrates the simplicity of passion. The quick, sketchy pencil movements allude to the sense of time fleeting in the face of the AIDS epidemic.

Robert Mapplethorpe’s photograph of Lisa Lyons is of great significance for the non-binary community. The photograph shows the first woman bodybuilder dressed as a mobster from the 1920s, indicating an act of defiance in the face of gender stereotypes and heteronormativity.

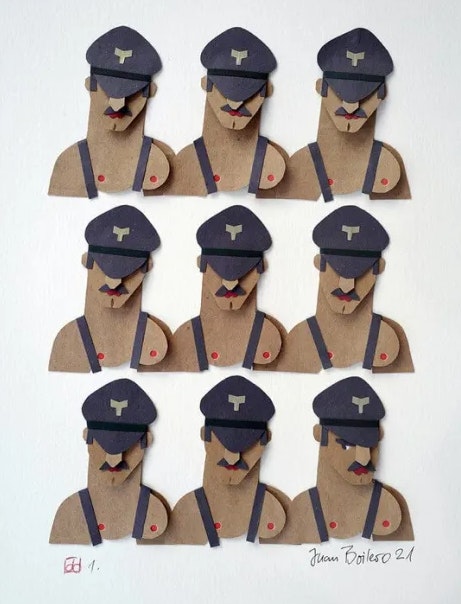

Juan Boilero’s La Miranda (2021) uses clever decoupage to explore and illustrate male sexuality. The three seemingly identical men cut out of cardboard grace this piece, and it may take you a moment to find a slight alteration in the pattern. The man’s charged gaze sets him apart from the uniformity of the image and invites us into the world of individual identity.

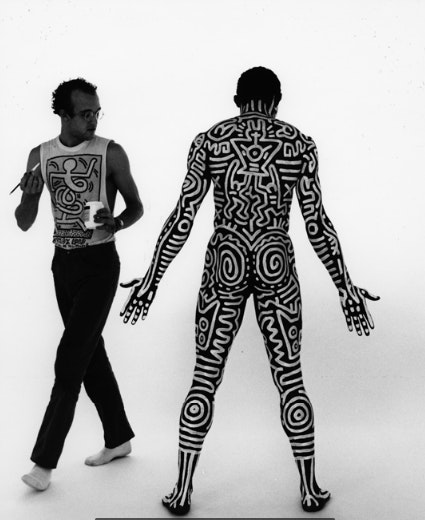

Keith Haring: Bill T. Jones Body Painting by Keith Haring (1983). Keith Haring is one of those people whose name you should remember. The man was a staunch activist for LGBTQ+ rights and a revolutionary in art. His dismissiveness of typical canvases also stands for his refusal to conform to heteronormative standards. Haring used human bodies as canvases in some of his projects as a metaphor for bodies telling stories, which, much later, became a new trend in performance arts too.

The Right Wing: Famous LGBTQ+ Artists

We cannot let you leave our museum without knowing at least a couple of the most influential and impactful LGBTQ+ artists (apart from Keith Haring, of course).

Robert Mapplethorpe (1946–1989). Mapplethorpe was one of the more controversial figures in the art scene. His work often sparked debate (we did say art was fairly radical), and he often discussed matters of art funding and challenges the LGBTQ+ community faced in the post-war years. His death, among countless others, was the direct result of the unethical governmental response to the AIDS epidemic.

Oreet Ashery is a contemporary London-based artist who discusses cultural and gender politics through her art. She uses her alter ego, Marcus Fisher, an orthodox Jewish man, to spark political debates on matters of non-binary identity and queer feminism. Her newest project deals with the digital afterlife, and you can hear more about it in Ashery’s web series Revisiting Genesis.

David Wojnarowicz (1954–1992). Wojnarowicz was one of the more influential avant-garde figures of the American art movement. He used mixed media inspired by street art and graffiti to illustrate the personal and global struggles of LGBTQ+ people. He weaved his personal experiences and fight with AIDS in pieces like Untitled (Buffalo), Peter Hujar Dreaming/Yukio Mishima: St. Sebastian, and I Feel a Vague Nausea. Wojnarowicz was very vocal in his political activism, often condemning social injustice surrounding the Lavender Scare before succumbing to an AIDS-related illness in 1992.

Alison Bechdel, a graphic novelist and cartoonist, presented her ground-breaking art that is still happily studied in literature departments these days. Her long-running comic, Dykes to Watch Out For, depicts lesbian life in the early 2000s, whereas her memoir Fun Home: A Family Tragicomic gives a more intimate view into her own experiences.

Wu Tsang. This Chinese-Swedish-American artist is best known for her short videos that explore gender-fluidity and queer subculture. Her documentary Wildness, which received critical appraisal at the Sundance Festival, shows life in a Los Angeles trans bar called Silver Platter. The film criticises stereotypes and prejudices against trans people.

While heading for the shop, remember Oscar Wilde, one of the true pioneers of the queer art scene. Wilde’s unapologetic attitudes paved the way for freedom of expression and LGBTQ+ artists’ self-actualisation.

Café and Shop: Powerful LGBTQ+ Art

You should grab a cup of coffee because you’re invited to think about the following while sipping your drink: what makes LGBTQ+ art powerful?

Is it the activism? Is it the frontier aspect, breaking boundaries and dispersing hatred, or is it pure aesthetics? There’s a bit of everything, but most importantly, it’s its variety of subtextual cues: resistance, resilience, bravery, loss, isolation, belonging, and a strong sense of justice.

LGBTQ+ artworks are never one-dimensional. They are deep and thought-provoking, meant to inspire and amaze. But they also exist to raise awareness and criticise. These masterpieces aim to bring people together, the LGBTQ+ community and allies alike, and unite them under one language that we all understand: art.

I hope you’ve enjoyed your museum tour. We hope to see you again soon!

LGBTQ+ art is any work of art that has LGBTQ+ themes at its core: representation, social justice, acceptance, belonging, identity negotiations or a call to activism, and alliance.

LGBTQ+ art sparked a social revolution towards achieving equal rights. From artwork negotiating queer identity by people like Oscar Wilde, to photography documenting the gay rights movement, to paintings and pictures responding to the AIDS crisis, LGBQT+ art is important because it empowers and promotes social justice.

Some of the most famous LGBTQ+ artists include Keith Haring, Gilbert Baker, Alison Bechdel, David Wojnarowicz, and Andy Warhol.

Queer art theory focuses on reading queer texts and arts in terms of how they reclaim queer spaces, subvert them, and react to social acts of denormalising queerness.

How we ensure our content is accurate and trustworthy?

At StudySmarter, we have created a learning platform that serves millions of students. Meet the people who work hard to deliver fact based content as well as making sure it is verified.

Gabriel Freitas is an AI Engineer with a solid experience in software development, machine learning algorithms, and generative AI, including large language models’ (LLMs) applications. Graduated in Electrical Engineering at the University of São Paulo, he is currently pursuing an MSc in Computer Engineering at the University of Campinas, specializing in machine learning topics. Gabriel has a strong background in software engineering and has worked on projects involving computer vision, embedded AI, and LLM applications.

Get to know Gabriel